Suse Bauer, Wohnstatt der Steine

11. September - 10. November 2021

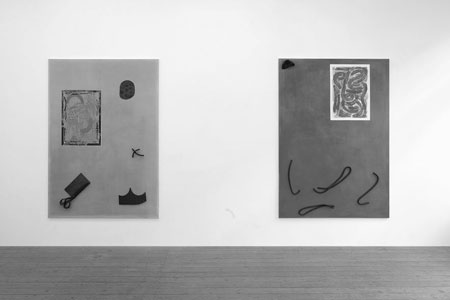

exhibition views

Conversation between Suse Bauer and Elena Conradi on the exhibition Wohnstatt der Steine

In your new exhibition, three skewed plinths with undulating profiles draw the visitor’s attention. The exhibits displayed on them might be sculptures, but they also read as models. Compared to the sharp-edged plinths, their surfaces seem raw and porous. Are these submissions to an art-in-architecture contest? Or are they inchoate modernist architectural visions, perhaps meant for transposition into a different scale, to a different place …? Wohnstatt der Steine, Abode of the Stones—the title seems to suggest as much.

In my imagination, I conceived them as models of monumental structures, with a forbiddingly compact and vaguely oppressive aura. I thought it was key to leave the scale and function undetermined. I made Wohnstatt der Steine in 2019, after an extended trip to Israel. I looked at the brutalist architecture all over that country because I was interested in the urbanistic formal vocabulary of what was once a society of pioneers and in particular because of what I see as parallels to the formal idiom of East German architecture. The difference being that the Israelis made much more extensive use of concrete, which stands there in that insane heat. I’m curious about how people envision the future. So I took sculptor’s clay, which when wet is reminiscent of washed concrete or very rough rendering, and rolled it into slabs, which later turned into these sculptures.

I think of Wohnstatt der Steine as design drawings from archives translated into a plastic medium. For buildings that were never realized. Because the times and situations changed before they could be, or because realization proved illusory or hubristic.

I’m interested in the socialist large-scale construction project as an image and stage in two works of literature in which it becomes a screen on which the failure of a utopian vision hobbled by hierarchies and bureaucratic institutionalization plays out. The novel “Trace of Stones,”(1) which came out in East Germany in 1964, supplied Heiner Müller with motifs for his play “The Construction Site,”(2) written that same year. Müller himself described his play, which was barred from publication until 1980, as being “about how the utopia ravages the landscape.” Andrei Platonov’s novel “The Foundation Pit, (3) completed in 1930, was not published until 1987 due to censorship. It tells the story of a gigantic proletarian construction project that aspires to build nothing less than a future of happiness for humankind; to be achieved by universal collaboration and manual labor, it founders under the burden of its purpose.

Your works in many ways play on dimensionality, polysemy, and latency. The same, for that matter, is true of the Makers and Takers—the oversized and oddly distorted ceramic coins or apple slices on the showroom’s walls. Relations of scale feel simulated and negotiable. Everything lingers in a status of conditional validity, awaiting the next update. Perhaps this unfinished and preliminary quality is also one explanation for why the clay objects in Wohnstatt der Steine were fired only once, without the final glost firing that sets the material’s form?

I prefer the term constructions, and yes, that’s true. These constructions are possibilities, being preliminary is part of their nature, they are frozen in a state of nascency.

Constructions, then. Another ceramic work in the exhibition—a relief-like wall piece made of glazed clay—is titled Wohnscheibe (Residential Slab Block), a recognizable allusion to generic prefabricated housing structures in East Germany. Wohnstatt der Steine, by contrast, is an artistic exploration of the idea of architecture as a political vision. The buildings of industrial modernity with their aesthetic and functional standardization of architectures reflect a social compact that subordinates the singular to the common good. Then, with the fall of the Wall, the associative framework around construction sites shifted. Residential living cast in concrete nowadays satisfies urban elites’ need to signal distinctiveness.

The (prefabricated) housing estate figured prominently in my parents’ personal lives and careers: both were civil engineers and worked in slab prefabrication. The apartment on the periphery they moved into with us children in 1980 was modern, in contrast with the derelict old city center. Everything looked the same, so we painted our balcony in colors. That way, I could point out where we lived to my friends from the playground. The insides of these residential slab blocks then accommodated the ‘new man’ with his individual desires in terms of interior design: wood paneling, wall-size Caribbean-beach poster, cuckoo clock. Later on, my childhood was also set on the building sites of the reunification era; my parents started a construction company and, in 1991, moved us into central Erfurt. The renovations that were proceeding apace all around us are now complete: the city has a neatly restored medieval center. The prefabricated housing estates have been partly “unbuilt” and, especially in the periphery, have become scenes of the social tensions prompted by the societal fractures of the “East German society-in-transformation.”(4)

The title sounds programmatic, bringing utopistic statist housing and urban planning conceptions to mind: Abode of Stones might be a working title for a major design contest for new public facilities, buildings or monuments, making your show a presentation of the winning submissions.

Yes, but I think there’s an ambivalence, even an edge of sadness. These stones, they are, well, petrified, fixed. The only thing they may yet become is dust. When I meditate on the title, I see a devastated landscape.

September 2021

1)Erik Neutsch, Spur der Steine, Halle: Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 1964.

2)Heiner Müller, Der Bau (1964), 2018.

3)Andrei Platonov, The Foundation Pit (1930/1987), New York Review of Books 2009.

4)Steffen Mau, Lütten Klein, Suhrkamp 2020.

--

In deiner neuen Ausstellung ziehen drei verzerrte Sockel mit wellenförmigem Profil die Aufmerksamkeit auf sich. Die Exponate, die sie präsentieren, könnten Skulpturen oder genauso gut Modelle darstellen. Ihre Oberflächen wirken gegenüber der Scharfkantigkeit der Podeste irgendwie rau, porös. Sind hier Entwürfe eines Kunst-am-Bau-Wettbewerbs ausgestellt? Oder handelt es sich um modernistische Bauideen, angedacht möglicherweise zur Übertragung in einen anderen Maßstab, an einem anderen Ort …?

Wohnstatt der Steine – der Titel scheint dies anzudeuten.

Ich hatte sie in meiner Vorstellung als Modelle von Monumentalbauten gedacht, irgendwie ungebrochen und bedrückend. Mit war wichtig, dass Maßstäblichkeit und Funktion offenbleiben. Wohnstatt der Steine entstand 2019, nach einer längeren Israelreise. Ich habe mir brutalistische Architektur überall im Land angesehen, da mich die bauliche Formenwelt der einstigen Pioniergesellschaft interessierte, auch und gerade wegen einiger Parallelen zur Formensprache von DDR-Architektur. Nur dass hier der Beton viel umfassender verwendet wurde und in dieser irrsinnigen Hitze steht. Mich interessieren Vorstellungen von Zukunft. Mit diesem Bildhauerton, der in feuchtem Zustand an Waschbeton oder sehr groben Putz erinnert, habe ich Platten gewalzt, aus denen später diese Skulpturen wurden.

Ich stelle mir vor, Wohnstatt der Steine sind ins Plastische übertragene Entwurfszeichnungen aus Archiven. Für Bauten, die nie umgesetzt wurden. Weil die Zeiten und Verhältnisse sich vorher änderten oder die Umsetzung sich als illusorisch und anmaßend erwies.

Mich interessiert die sozialistische Großbaustelle als Bild und Bühne in zwei literarischen Werken, in denen sie zur Projektionsfläche für das Scheitern der Utopie an Hierarchie und bürokratischer Institutionalisierung wird. In der DDR erschien 1964 „Spur der Steine“,(1) ein Roman, nach dessen Motiven Heiner Müller 1964 das Stück „Der Bau“(2) schrieb. Es war bis 1980 verboten und Müller selbst bezeichnete es als „ein Stück über die Zerstörung der Landschaft durch Utopie“. Andrej Platonow schrieb 1930 „Die Baugrube“(3), einen Roman, der wegen der Zensur erst 1987 erscheinen konnte. Darin geht es um ein gigantisches proletarisches Bauprojekt, das sich nichts Geringeres als die glückliche Zukunft der Menschheit zum Ziel gesetzt hat und dies durch das Mitwirken Aller und ihrer Hände Arbeit erreichen will, aber an der Last der Aufgabe scheitert.

In deinen Arbeiten sind die Dinge auf Dimensionalität, Mehrdeutigkeit und Latenz angelegt. Das gilt ja übrigens auch für Makers and Takers – die überdimensionalen und verzerrt wirkenden Geldmünzen oder die Apfelscheiben aus Keramik an den Wänden des Ausstellungsraums. Größenverhältnisse wirken simuliert, verhandelbar. Alles befindet sich in dem Status bedingter Gültigkeit, bereit für das nächste Update. Vielleicht ist das Entwurfhafte auch eine Erklärung dafür, warum bei Wohnstatt der Steine die Tonobjekte nur einmal gebrannt wurden, ohne den finalen, das Material festigenden Hochbrand?

Ich ziehe den Begriff Bauten vor, und ja, das ist so. Diese Bauten sind Möglichkeiten, ihre Vorläufigkeit ist ihnen eingeschrieben, sie sind im Werden festgehalten.

Bauten also. Während eine andere Keramikarbeit aus der Ausstellung – eine reliefartige Wandarbeit aus lasiertem Ton – durch ihren Titel Wohnscheibe konkret auf die generischen Plattenbauten der DDR anspielt, ist Wohnstatt der Steine eine künstlerische Annäherung an die Idee von Architektur als politischer Vision. In den Bauten der Industriemoderne drückte sich in der ästhetischen und funktionalen Standardisierung der Architekturen die gesellschaftliche Übereinkunft darüber aus, das Singuläre dem Gemeinwohl unterzuordnen. Dann änderten sich auf den Baustellen der Wendezeit die Zuschreibungen. In Beton gegossenes Wohnen befriedigt heute das Distinktionsbedürfnis urbaner Eliten.

Das Projekt Plattenbau- oder Neubausiedlung war für meine Eltern persönlich und beruflich bedeutsam, beide arbeiteten als Bauingenieure in der sogenannten Plattenvorfertigung und die Wohnung am Stadtrand, in die sie 1980 mit uns einzogen, war im Gegensatz zur zerfallenen Altstadt modern. Es sah alles gleich aus, deshalb haben wir unseren Balkon mit Farben angestrichen. So konnte ich meinen Freundinnen vom Spielplatz aus zeigen, wo ich wohne. In den Innenleben dieser Wohnscheiben war dann Platz für die individuellen Einrichtungsbedürfnisse des ‚neuen Menschen‘: Holzvertäfelungen, Karibik-Wandposter & Kuckucksuhr. Baustellen der Wendezeit waren später ebenso Orte meiner Kindheit, als meine Eltern eine Baufirma gründeten und wir 1991 in die Altstadt von Erfurt zogen. Überall wurde zügig saniert und nun ist sie fertig: die fein restaurierte Mittelalterstadt. Die Plattenbausiedlungen wurden teilweise “zurückgebaut“ und sind in der Peripherie vor allem zu Orten sozialer Spannungen geworden, die sich aus den sozialen Frakturen der „ostdeutschen Transformationsgesellschaft“(4) ergeben haben.

Der programmatisch klingende Titel lässt an utopistische staatliche Wohnungs– und Städtebaukonzepte denken: Wohnstatt der Steine könnte ein Arbeitstitel lauten, für eine großangelegte Ausschreibung neuer öffentlicher Anlagen, Gebäude oder Denkmäler, die hier als Entwürfe vorgestellt werden.

Ja, aber ich finde er ist ambivalent, traurig fast. Diese Steine, sie sind eben versteinert, fest. Alles, was sie noch werden können, ist Staub. Wenn ich über den Titel nachdenke, denke ich an wüste Landschaft.

Hamburg, September 2021

1) Erik Neutsch, Spur der Steine, Halle: Mitteldeutscher Verlag 1964.

2) Heiner Müller, Der Bau (1964), 2018.

3) Andrej Platonow, Die Baugrube (1930/1987), Suhrkamp 2016.

4) Steffen Mau, Lütten Klein, Suhrkamp 2020.

Suse Bauer, Lazy Poet Read A Book

27. March - 9. May 2015

exhibition views

In her exhibition Lazy Poet Read a Book Suse Bauer presents a set of new works. Coins, blanking chads, nails, worm-shaped ceramic curls, and similar detritus add up to a subjective collection that might have its origin in the artist’s studio, in a personal interest in anthropology, or in an effort to build a record of a history. Together with pictures and fragments of pictures, these elements are arranged on five large monochrome primed canvases on metal backings and held in place by magnets. The various components form temporary ensembles that reveal closer or more distant affinities and read as pictorial proposals the artist offers the viewer. The ceramic objects evince traces of their manual facture; they are bits and pieces isolated from the physical context of the studio in which they figured as tools or residues of the creative process. The painted pieces of canvas as well as the paper monotypes—a printing technique in which only a single print is made from a plate, producing a unique work of art—serve as visual media duplicating the canvas, reducing the latter to the status of a colorful backdrop.

As in earlier works by Bauer, similar objects appear several times over in the arrangements, functioning in different ways in the respective visual contexts. Yet the magnetic fixation of the objects on the canvas leaves the arrangement open to modification, turning the index of the artist’s manual intervention into a compositional proposal, a status quo between random configuration and signifier that operates on different scales.

The compositions, moreover, are now created in the horizontal register: laid out flat on the ground, the canvas acts as a segment of floor or the surface of a desk or drafting board, to be subsequently set upright like a painted panel. This approach has its origin in Bauer’s use of the scanner, with which she turned various paper and cardboard arrangements into digital collages she then printed out to make wall pictures. Calling the picture plane a “flatbed” (Leo Steinberg introduced the term in “Other Criteria” with reference to Robert Rauschenberg’s work, alluding to the printing press’s flatbed) has been one way since the advent of postmodernism to describe the ways artists have used the visual support medium for purposes other than the illusion of depth: as surfaces on which diverse information can be placed and assorted.

The metaphor of the computer display as a desktop builds on the same conception of the visual surface; our habits of seeing have adapted to the idea of the monochrome flatbed as a user interface on which information is collated. Suse Bauer’s arrangements transform that interface into the scene of an artistic gesture that acknowledges the need for sorting but defies the attempt to impose a univocal reading.

Curated by Rebekka Seubert, two guided tours of the exhibition have been held on April 8 from 6 to 7pm. The archaeologist Kay-Peter Suchowa, who will excavate the foundations of the old city wall and the earliest Church of Saint Nicholas on Hopfenmarkt until June, and the philosopher Roger Behrens, who studies critical theory and the aesthetics of postmodernism, shared their particular perspectives on the exhibition with the audience.

DE

Die Ausstellung Lazy Poet Read A Book zeigt neue Arbeiten von Suse Bauer. Münzen, Stanzreste, Nägel oder zu Würmern gerollte Keramiken bilden in der Ausstellung eine subjektive Sammlung deren Ursprung genauso das Atelier, wie ein persönliches Interesse für Anthropologie und eine Vergewisserung über die Geschichte sein kann. Auf fünf großformatigen, monochrom grundierten Leinwänden mit metallischer Rückseite sind sie gemeinsam mit Bildern und Bildfragmenten durch Magnete fixiert und arrangiert. Diese verschiedenen Elemente bilden ein temporäres Gefüge, stehen in enger oder entfernter Nachbarschaft zueinander und lesen sich als Bildvorschlag der Künstlerin an den Betrachter. Die Keramikobjekte tragen die Spuren des manuellen Fertigungsprozesses und sind als Fragmente herausgelöst aus dem physischen Zusammenhang des Ateliers, wo sie als Handwerkszeug oder Spur von Arbeit kontextualisiert waren. Die bemalten Leinwandfragmente, sowie die auf Papier gedruckten Monotypien – ein Druckverfahren zum einmaligen Gebrauch, bei dem das Druckerzeugnis Unikat bleibt – doppeln als Bildflächen die der Leinwand, sodass diese damit nur als farbiger Hintergrund dient.

Wie schon in früheren Arbeiten, tauchen wiederholt ähnliche Gegenstände in den Arrangements auf und funktionieren im jeweiligen Bildkontext auf verschiedene Weise. Doch durch die immer wieder veränderbare, magnetische Fixierung der Gegenstände auf der Leinwand wird die Handschrift der Künstlerin zum Angebot einer Komposition, ein status quo zwischen Zufall und Zeichen, der unterschiedlichen Maßstäben gehorcht. Außerdem entstehen die Bildkompositionen nun im Horizontalen: Flach auf den Boden gelegt, entspricht die Leinwand einem Bodensegment, einer Schreibtischoberfläche oder einem Reisbrett und wird erst im späteren Prozess aufgerichtet zum Tafelbild. Diese Arbeitsweise ist ursprünglich am Scanner entstanden, wo Suse Bauer unterschiedliche Papier und Pappe-Arrangements zu Collagen eingescannt und ausgedruckt wieder zu Wandbildern gewandelt hat. Die Bildoberfläche als "flatbed" zu bezeichnen (Leo Steinberg benutzt diesen Begriff zu Robert Rauschenberg in "Other Criteria" und bezieht sich dabei auf das Flachbett der Druckerpresse) ist seit der Postmoderne Mittel gewesen, um zu beschreiben, wie Künstler die bildtragende Oberfläche anders als einen Illusionsraum verwenden: als Flächen auf denen verschiedene Informationen angeordnet und sortiert werden können. Auch die Schreibtisch-Metapher des Computers als Desktop hat diese Vorstellung der Bildfläche aufgegriffen, sodass unsere Sehgewohnheiten sich angepasst haben an eine Vorstellung des monochromen Flachbetts als Benutzeroberfläche zum Sortieren von Information. Die Arrangements von Suse Bauer wandeln diese um in eine künstlerische Geste, die trotz eines Bedürfnisses nach Sortierung keine eindeutige Lesart ergeben kann.

In diesem Zusammenhang wurden am 8.April von 18-19 Uhr zwei aufeinanderfolgende Führungen angeboten. Der Archäologe Kay-Peter Suchowa, der bis Juni am Hopfenmarkt die Fundamente des alten Stadtwalls und der ersten Nikolaikirche ausgräbt und der Philosoph Roger Behrens, der sich mit der kritischen Theorie sowie mit der Ästhetik der Postmoderne beschäftigt, haben jeweils ihre Sicht auf die Ausstellung geteilt.

Das Rahmenprogramm wurde kuratiert von Rebekka Seubert.

Suse Bauer, Zukunft löst sich auf in Gegenwart

27. October - 24. November 2012

exhibition views

In Suse Bauer’s works, material, form, and color take the helm and direct the conception. The evolution of form is guided by the physicality of the clay and the chromatic values of the oil crayons in an experimental quest for depth and dynamic potential. What Bauer does is not painting in the classical sense but, as she sees it, a sort of construction design drawing, a preliminary stage or description of possible sculptural work. The techniques she brings to the material are adopted from manual crafts and artisanship: the sgraffito, a fresco technique known since the Renaissance that has largely fallen out of use, and the work with clay, which presents an opportunity for hands-on expressive and creative design. Beyond material qualities and techniques, form and composition play a central part in Suse Bauer’s art. The same shapes appear again and again in different colors and positions. The series of eight medium formats systematically maps this interplay of recurring forms and colors and their composition, unfolding a dynamic dialogue between figuration and abstraction. The ceramics also transform concrete tools—the very means of production—into abstract shapes. They do not tell stories or function as a facile referential system or symbol but instead make production itself the subject of the work. They visualize the artist’s practice as a process of appropriation and the evolution of form implicit in it, which always also leaves room for improvisation.

DE

Suse Bauer’s works come into being in accordance with the principle that making is thinking. Her production is not a means to an end but instead the point of departure of her work and the problem it addresses; Bauer explores “how the work of the hand can inform the work of the mind.” The simultaneity of thinking and making defines her art. The idea is at once: construction and cognition. The works contain splinters of the visions of classical modernism as well as elements of East German vernacular culture and echoes of Sumerian stone tablets. The title of the exhibition points to the present day: planning horizons shrink and biographical designs have short lifespans in today’s crisis-ridden late modernity—the future dissolves into the present.

In Suse Bauers Arbeiten übernehmen Material, Formen und Farben die Regie in der Konzeption. Die Formfindung entsteht aus der Materialität des Tons, der Farbigkeit der Ölkreiden und sucht experimentierend nach Tiefe, einem Spannungsverhältnis. Sie sind keine Malerei im klassischen Sinne; Bauer versteht sie vielmehr als Konstruktionszeichnungen, als Vorstufe zu oder Beschreibung möglicher Skulptur. Die Techniken für die Arbeit mit dem Material eignet sich Bauer aus Handwerk und Kunsthandwerk an: das Sgraffitto, eine Frescotechnik, die seit der Renaissance verwendet wird und heute nur noch selten Anwendung findet, sowie das Arbeiten mit Ton, das eine unmittelbare Möglichkeit zu Ausdruck und Gestaltung ist. Neben Materialität und Technik spielen Formen und die Komposition eine zentrale Rolle in Suse Bauers Arbeit. Immer wieder tauchen dieselben Formen in unterschiedlichen Farben und Positionen auf. In der Serie der acht Mittelformate wird dieses Zusammenspiel von sich wiederholenden Formen und Farben und ihrer Komposition durchdekliniert und es entfaltet sich so ein Spannungsfeld zwischen Figuration und Abstraktion. Ebenso werden in den Keramiken konkrete Werkzeuge – die Mittel der Produktion selbst – zu abstrakten Formen. Sie erzählen keine Geschichten oder fungieren vordergründig als Referenzsystem oder Symbol, sondern sie machen die Produktion selbst zum Subjekt der Arbeit. Sie visualisieren die künstlerische Praxis als Aneignungsprozess und die ihm innewohnende Formfindung, die immer auch Improvisation zulässt.

Suse Bauers Arbeiten entstehen nach dem Prinzip des Making is Thinking. Die Produktion ist hier nicht Mittel zum Zweck, sondern vielmehr Ausgangspunkt und Thema der Arbeit; Bauer ergründet „how the work of the hand can inform the work of the mind“. Ihre Arbeit ist durch die Gleichzeitigkeit von Denken und Machen gekennzeichnet. Der Gedanke ist zugleich: Bauen und Erkennen. Die Arbeiten tragen Momente der Visionen der klassischen Moderne ebenso in sich wie Elemente ostdeutscher Alltagskultur und Anklänge an sumerische Steintafeln. Und der Titel der Ausstellung verweist auf das Heute: Planungszeiträume schrumpfen und biografische Entwürfe haben eine kurze Lebensdauer in der Gegenwart der krisenhaften Spätmoderne – Zukunft löst sich auf in Gegenwart.

Suse Bauer, Alles was von mir Ich genannt wird

10. April - 15. May 2010

In this latest exhibition, Suse Bauer presents a wall relief in addition to pictures, sculptures and ceramics. Pastose and oil paints are layered one atop the other in Bauer’s works, directly by hand and primarily with the use of templates. The tactile quality and relief-like character of the resultant abundance of surface structures emphasizes the malleability and plasticity of the works. These abstract, largely geometric compositions possess an enormous intensity of expression and poignant immediacy. They work their way into the three-dimensional space, establishing a place for themselves in terms of both form and material content.

Bauer’s use of distinctly modernist aesthetic characteristics encompasses a direct and intentional reference to the great efforts involved in mapping out a utopia; every single element, it seems, is complicit in the aim to communicate a vision, and the pursuit of culmination subsumes every last detail. In the face of such a quest, the design sketch – an embodiment of the state of instability – is itself the artwork. It does not strive for consummate perfection; rather, with its formal strictness and the decisiveness of its sculptural gestures, it asserts itself as a highly dynamic transitional moment. This sense of vitality and intention is distinctly present in the exhibited works, which feature a remarkable presence and subjective nature.

The artist employs numerous resources to create her own symbolic language of pictures and emblems in candidly impartial contravention of their actual historic and cultural context. She redefines things, resituates contexts and, in the end, describes things from the subjective perspective of her individual life experience. Bauer’s deeply personal involvement is key to the creative process of forging and mapping out her own originative path as she concretely manipulates materials, forms and composition. She develops her own unique heraldic crest – one which reaches beyond any rationality or functionality, defies clear-cut interpretation and remains visionary.

DE

Suse Bauer zeigt in ihrer neuen Ausstellung ein Wandrelief sowie Bilder, Skulpturen und Keramiken. Direkt mit der Hand und meistens unter Verwendung von Schablonen wird die pastose und ölige Farbe in Schichten aufgetragen. Es entstehen vielfältige Oberflächenstrukturen, deren haptische Qualität und Reliefcharakter die Plastizität der Bilder betont. Die abstrakten und weitestgehend geometrischen Kompositionen besitzen eine enorme Ausdruckskraft und Unmittelbarkeit. Sie konstruieren sich sowohl formal als auch materiell in den dreidimensionalen Raum hinein. In der Aneignung modernistischer Ästhetikmerkmale liegt ein gezielter Verweis auf die Formulierungsbemühungen einer Utopie - jedes einzelne Element, so scheint es, arbeitet auf den Beschreibungsversuch einer Vision hin. Alles befindet sich in diesem Prozess der Realisierung. Dabei ist der Konstruktionsentwurf, der instabile Zustand selbst das Werk. Es strebt nicht an, Vollendung zu erlangen, es behauptet sich in seiner formalen Strenge und der Entschiedenheit der bildhauerischen Geste als hochdynamisches Übergangsmoment. Diese Vitalität und Absicht überträgt sich auf die ausgestellten Arbeiten, deren Präsenz und Subjektivierung bemerkenswert ist.

Dem genauen historischen und kulturellen Kontext gegenüber unvoreingenommen bedient sich die Künstlerin zahlreicher Ressourcen für die Erfindung eigener symbolhafter Bildsprachen und Zeichen. Sie deutet um, verschiebt Kontexte und beschreibt schließlich aus der subjektiven Perspektive ihrer Lebenspraxis. Dieses Hervorbringen einer eigenen Ebene bezieht die persönliche Involviertheit als grund-legende Bedingung in die physische Auseinandersetzung mit Material, Form und Komposition mit ein. Die Künstlerin entwickelt eine Heraldik jenseits von Rationalität und Anwendbarkeit, die sich jeder Eindeutigkeit der Interpretation verweigert und Vision bleibt.